Did Busing Really Change Our Schools?

Questioning the real drivers of student success – is it the school or the support system? Or Both!

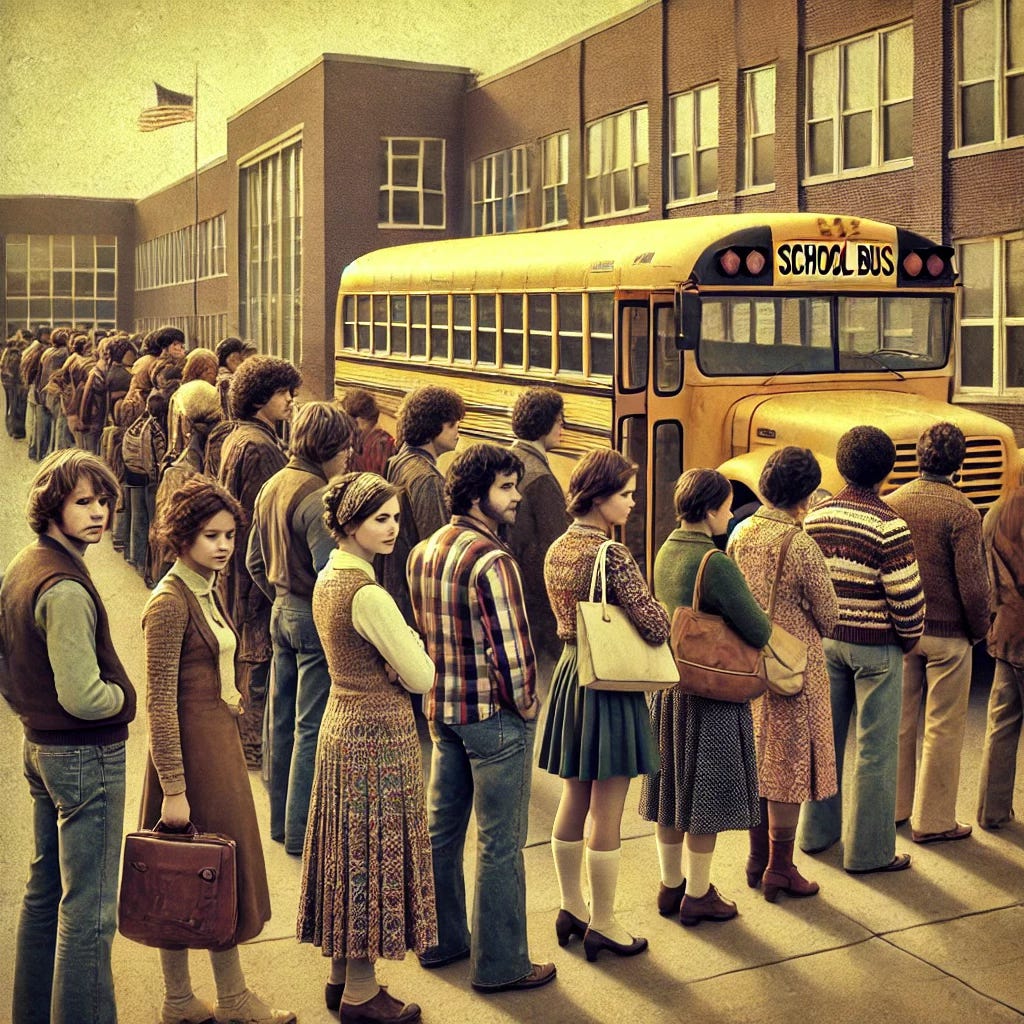

Busing was one of those ideas that seemed straightforward: bring kids from different backgrounds into the same schools to achieve racial balance. But in the 1970s, it wasn’t just about getting kids from point A to point B; it was about trying to undo generations of segregation and discrimination in a single bold move. The reality, though, was a lot messier than the theory.

I remember it from my high school days at Manchester High School, where kids were bused in from Hartford, Connecticut. It was a daily reminder that “fixing” inequality wasn’t as simple as just bringing people together. Even then, I wondered: did it really make a difference? Did transporting kids across a few towns solve the real issues at hand? I don’t think it was ever that clear.

Let’s step back for a second. Busing was the federal government’s response to deep-seated segregation in American schools, especially in the South. Even though the Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education back in 1954 that separate schools were unconstitutional, integration was still slow and resisted by many, and decades of racist housing policies and neighborhood redlining had created schools that were overwhelmingly white or Black, rich or poor. Busing was supposed to level the playing field, taking students from predominantly Black neighborhoods to predominantly white schools and vice versa.

For Black families, busing seemed like a shot at a fairer education. It was a chance for their kids to attend better-funded schools, get smaller class sizes, and maybe, just maybe, break out of the cycle of poverty. But for many white families, it felt like an invasion. Suddenly, their children were being sent across town to neighborhoods they’d never visited and schools they didn’t choose. Busing wasn’t just disruptive – it threatened their control over their children’s education.

Boston’s busing controversy in 1974 became the prime example of just how divided people were. A federal judge ordered Boston to bus students to balance out the racial demographics, and the reaction was explosive. White families protested, sometimes violently, feeling that their neighborhoods were under siege. They saw it as the government stepping in to upend their lives without asking. And maybe, in some ways, they were right to feel that way. For all the good intentions behind it, busing was a top-down solution that didn’t ask communities what they thought – it simply imposed itself.

And here’s where it gets even more complicated. I often think about the schools near me now in the Bronx, just down the street from each other – DeWitt Clinton High School and Bronx Science. Clinton is a local public school that serves a diverse, primarily Black and Hispanic student body, with students from all kinds of backgrounds and levels of academic preparation. Many students face tough challenges both inside and outside of school, and Clinton is doing its best with what it’s got. Then there’s Bronx Science, one of New York City’s elite specialized high schools, where students must pass a rigorous entrance exam to get in. It’s got the resources, the reputation, and the high academic standards.

But what if we swapped the students from each school? Would Clinton’s kids automatically excel at Bronx Science because of the fancy name and advanced resources? Maybe a few of them would thrive with the extra support, but would all? And if we sent Bronx Science students to Clinton, would their performance plummet, or would they hold steady because of the habits and support systems they’ve built? We could even try switching the teachers – put Bronx Science teachers in Clinton and Clinton teachers in Bronx Science. Would we suddenly see a major shift in achievement? Or would they all face the same challenges of limited resources and the reality of different home environments?

What if the core of the issue isn’t about which school the kids go to but what’s happening in their homes and communities? The support they get (or don’t get), the expectations set around education, and the sense of possibility are things that no amount of busing or policy can entirely fix.

So what did busing achieve? For some, it created real opportunities. Black students got access to better-funded schools; some could break out of the cycles that held their families back. But it also came at a cost. White families who didn’t want busing withdrew from public schools entirely, opting for private schools or homeschooling, which only led to new forms of segregation. The big idea behind busing was to create equality, but in many ways, it just re-segregated the school system in a different way.

Busing also left a deep scar on how Americans view government intervention. To a lot of families, it felt like the government was imposing its will on local communities without caring what they thought. That skepticism of government power didn’t go away; if anything, it fueled a rise in conservative politics in the 1980s and helped push Ronald Reagan into the White House. He was seen as the champion for local control, someone who would protect communities from what they saw as federal overreach.

Would busing alone ever be enough to fix the inequalities built up over generations? It could be more about the kids, the families, and the environment they come from. Maybe if we put as much effort into supporting communities and creating a culture of learning as we did into busing, we’d see the kind of change everyone was hoping for. Because in the end, the school building and the bus route might matter a lot less than what’s happening at home.

Clayton Craddock is a devoted father of two, an accomplished musician, and a thought-provoker dedicated to Socratic questioning, challenging the status quo, and encouraging a deeper contemplation on various issues. Subscribe to Think Things Through HERE, and for inquiries and to connect, email him here: Clayton@claytoncraddock.com.

Just another example of the vast and permanent chasm, between the high-minded-sounding political sentiments behind some kind of proposed government program, and the typically calamitous and unmanageable results of actually setting such a program in motion.

One would think that, in an adult reality which rewards applications of realism and common sense much more reliably than it rewards demands for the fruition of magical thinking, it would begin to occur to adults that nothing any government says is a good idea ever turns out in the real world to be any such thing.

For my own part, I spent most of the (less than twelve) I was compelled to waste on being locked up in a government institution, while remaining continually astonished that I could and did educate myself by my own prerogatives far better than those calling themselves 'teachers' had ever bothered to become, wishing somebody would burn the place to the ground, and spare me the burden of ever having to check myself into a day-prison for any more days of my life.

I never cared what color of skin anyone had, either among my peers or among the wardens and guards whose daily bread came from keeping these foul institutions open for business. All I ever cared about was freedom, my own or anyone else's, while continuing to be unable to ignore how anyone's freedom bore no relation to the results of this 'education' such houses of bureaucratic horror were supposed to be teaching anyone how to prepare for.